Categories: Seminar SS11

About monkey fingers and censorship

If companies do not show interest on serious stakeholder dialogue, it can have heavy influence to their reputation – the Nestlé case

Johannes Froschmeir, Nils Fröhlich (EMM SS2011, Integrierte Marktkommunikation Prof. Dr. Mödinger)

A bite in a chocolate bar, a horripilating crunch and blood running out of the mouth: by this scene taken from an internet video, Greenpeace caused a social media disaster for the Swiss food combine Nestlé. In spring 2010, the environmental group posted this movie on the web to criticize the deforestation of rainforests for the production of palm oil. It is needed for chocolate bars like Nestlé’s Kit Kat. But that would destroy the home range of the Orang-Utan, Greenpeace said. So in the video, an office-worker eats such a Kit Kat chocolate bar. But it is no ordinary sweetness: It turns out to be an Orang-Utan finger and the employee gets his mouth full of blood when he bites in it.

The reaction of Nestlé was to censor the video and to block web postings concerning this topic. The company stopped releasing any information. They even took their own Facebook fanpage offline. The result was a very heavy loss of reputation.

For sure, Nestlé didn’t expect this to assume such proportions. Maybe the reason was that the company did not attach enough importance to a non-governmental organisation like Greenpeace. But it is a stakeholder of the company as well as investors or customers. Because in the strategic understanding of stakeholders, all the people, groups and institutions who have influence on the company or those who are affected by the company are stakeholders. (Stößlein, Mertens 2006) The following explanations are going to explore how NGOs work and how the relationship towards companies in general can look like.

What are NGOs

Schubert and Klein define NGOs as organizations that act for transnational political, social, ecological and economical aims, based on private initiative. They take up a position in the process of political volition. That means they pool political interests, articulate and implement them. NGOs discharge these functions by setting the agenda for their aims, representing them beyond national borders and doing project work. The main subjects NGOs work on are development policy, human rights, humanitarian aid and ecology.

Areas of influence

Non-governmental organisations take influence on three areas: Society and the public by setting agenda in the media and change public opinion in their own interest. That is a very important point because it plays a role on handling with the two other areas: On the one hand, it makes it easier for lobbying in the politics and to carry through the own interests. On the other hand they can influence the economy by changing consumer’s shopping habits and opinions of companies (Schubert, Klein 2006).

How NGOs can interact with companies

In general, there are two ways for NGOs in their behaviour towards corporations. On the one hand there is the cooperative way. An example is the environmental group “World Wide Fund For Nature (WWF)”. They work together with companies and try to reach the consumers on this way. A well-known campaign was the so-called “Krombacher Regenwaldprojekt”. The German brewery promised to purchase and save a certain area of rainforest for every sold beer crate.

On the other hand, NGOs can act on the basis of confrontation. Greenpeace is famous for its high-publicity actions, for example to drive by rubber dinghies towards oil tankers. The Nestlé case was another example for this offensive strategy. It seems to prove that stakeholder dialogue is a matter which companies should pay a lot of attention. The Nestlé case moreover shows that the relationship towards NGOs needs a special kind of handling.

How companies interact with stakeholders

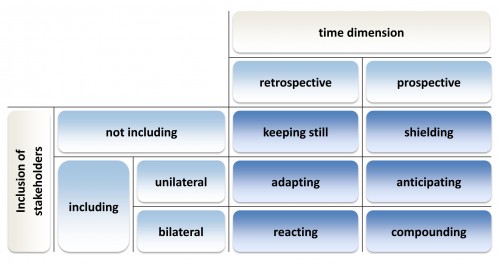

In practice, there are several ways how the relationship between corporations and stakeholders can be arranged. Thommen (2003) developed a matrix in which he mentions two dimensions of interaction. On the one hand, there is the involvement of the stakeholders by the corporations: Do they regard their stakeholders‘ requirements, for example better working conditions, or do they ignore them? And on the other hand, Thommen describes the temporal dimension: Do companies just communicate after stakeholders‘ reactions, for example if employees strike because of unbearable pollutions hazardous to health at their workplace? Or do they look ahead in their stakeholder dialogue and try to avoid such conflicts?

The following picture shows this model and its dimensions:

Source: Thommen 2003

If these two dimensions are connected, it equals six types of strategies, how can behave towards their stakeholders:

Keeping still: This type of communication is characterized by an exclusive orientation towards the company´s interests. If someone follows this policy, he accepts unethical behaviour of the corporation and also its consequences. No information is given outwards. Changes in this procedure only happen after strong pressure has been applied to them.

Shielding: Not to respect the stakeholders‘ demands, is a behaviour also used in this type of dialogue strategy. In that case, companies show their declining attitude towards them. Concerns rather try to mislead stakeholders, if they seem to be dangerous for the business interests.

Adapting: In this case, entrepreneurial acting is fitted to the stakeholders‘ claims. But this happens not until they articulated their requirements. So if companies choose this strategy too often, they will possibly lose their credibility.

Anticipating: To avoid such threats, it can be useful to proceed in a forward-thinking way and to gather future stakeholders‘ demands. Afterwards they have to be integrated into the corporate policy. But this strategy is unilateral. So if a company misses to discuss its findings with their stakeholders, it will possibly lead to misunderstandings.

Reacting: This is a similar strategy to “adapting”: Companies do not act until the stakeholders articulate their requirements. The difference is that afterwards concerns start to exchange views intensively. This runs the risk for them to act only when the conflict has already risen up. Then it will be very difficult to solve it.

Compounding: Companies that gather the claims of the stakeholders and additional involve them in finding solutions, will easier find a compromise. (Thommen 2003)

This type standardization of the varieties of interaction with stakeholders seems to grade from the worst case (“keeping still”) to the ideal case (“compounding”). Even non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have to do with these different types.

Nestlé’s strategy can be assigned to the first kind of stakeholder dialogue mentioned before, which is „keeping still“. Later on they changed their behaviour into „adapting“: After this affair, the company declared to stop working together with suppliers that deliver environmentally harmful palm oil.

Arenas of stakeholders

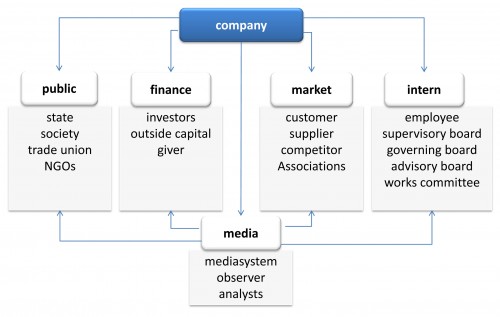

As mentioned in the introduction stakeholders are all groups that have influence on or are influenced by companies. The following passage gives an overview: Menz and Stahl (2008) arrange the different Stakeholders in arenas. Arenas are a conceptual or a real place, on which dialogue with the stakeholders can be hold. The focus will be on the stakeholders of the public arena.

Arenas of the Stakeholder dialogue (Source: Menz, Stahl 2008)

Public arena

NGOs belong to the public arena, as well as the state, society, trade unions. Related to the state, the company can try to take a passive role or an active one. Smaller companies often try to influence the close environment of their locations. Bigger companies rather act through lobbying or with personally contact to leading politicians.

The society is a lineup of people who have expectations of a company. These expectations are individually and ideologically influenced as well as from a cultural standpoint. Today the companies try to present themselves as corporate citizens to accomplish the expectations of the corporate social responsibility. Normally, the companies use the media for the representation of their corporate citizens.

In the stakeholder dialogue the company does not just take measures or use instruments. It is the process in which the company cooperates, forms coalitions, argues or sometimes ignores the stakeholders and their interests.

The “relevant milieu” of the company

Every systematic stakeholder management starts with the analysis of the groups of interests and stakeholders. The Stakeholders are ordered in A-, B- and C-stakeholders. The A– and B-stakeholders are the most important groups; the C-stakeholders normally do not take the focus of the dialogue, because of the influence they have. The A-stakeholders have a huge influence and they are talkative. The communication comes mostly directly from the management committee of the company. The B-stakeholders have also big power potential, but without showing openness. Here, the company tries to take more influence by using professional “relation promoters”. These promoters are people, who establish relations to organizations, fields of knowledge and cultures.

The objectives of the stakeholder dialogue

The stakeholder dialogue objective is not the representation of achievements; it is rather the dialogue to show contradiction. The participants should let exist different points of view side by side. Another important issue is to take new standpoints and to enlarge existing perspectives. The business management aims to construct durable relations to the A and B stakeholders.

The three dimensions of the stakeholder relationships

Stakeholder relationships are founded on three fragile dimensions. Robert Bosch once said: “Rather lose money than trust”. Trust needs time and includes the risk of disappointment. This is also valid for companies which must allow access to the organization. This can be achieved by the integration of customers or suppliers in the company and the well-known open house is also a possibility. Trust is therefore based on honesty; this does not mean falsifying announcements for the pushing of own interests. Even in the dialogue between companies and NGOs, the trust takes a more important role, because generally in such a relation a big distrust takes place. But there must be said that both mistrust and scrutinization are some of the main issues of the NGOs. Another dimension is the reputation, which is the sum of single expectations and experiences concerning the trustworthiness of an act. The last extent is the commitment: it is the readiness to stay in an existing relationship, even if there are rational better options available.

To sum up, stakeholder dialogue is an ambitious tool of business management. On the one hand, it is about the art of dialogue and not about self-projection. On the other, limited resources have to be divided in such a way that not only some stakeholders would take part in the communication. At last the business management has to get involved permanently with the three dimensions: trust, reputation and commitment.

What does that mean for human spirit marketing?

The foregoing explanations show that the principles of stakeholder communication have a lot to do with the concept of human spirit marketing. For instance, trust reputation and commitment can also be considered as a basis of the relationship between companies and stakeholders as well as for human spirit marketing. Furthermore, if companies don’t fulfill these principles towards one part of the stakeholders, it can have a negative influence on other ones. In the case of Nestlé, the censorship policy towards Greenpeace ruined its image and had a heavy loss of reputation in the view of many consumers. Because of Nestlé’s information firewall, they couldn’t trust anymore in the communication of this major corporation. And also the slogan „Have a break“ didn’t give an emotional fulfillment anymore, because Nestlé didn’t straighten out the slogan’s strain by Greenpeace. That proves that stakeholder dialogue and human spirit marketing are linked very strong. (Menz, Stahl 2008)

Literature:

Menz, Florian; Stahl, Heinz K.: Handbuch Stakeholderkommunikation. Berlin: Erich Schmidt Verlag GmbH & Co 2008

Schubert, Klaus; Klein, Martina: Das Poltiklexikon. Bonn: Dietz 2006

Stößlein, Marin; Mertens, Peter: Anspruchsgruppenkommunikation. Wiesbaden: Deutscher Universitäts-Verlag; GWW Fachverlag GmbH 2006

Thommen, Jean-Paul: Glaubwürdigkeit und Corporate Governance. Versus 2003

10 Mai 2011 admin